На русском языке

Gravitational

model of strong interaction

Gravitational model of strong

interaction is the

model, in which strong interaction is described by strong gravitation, the action of gravitational torsion field and

electromagnetic forces.

Contents

|

Standard theory

In elementary particle physics the generally accepted

model is the Standard model according to which strong interaction occurs on the

scale, not much greater than the size of atomic nuclei. In this case, there are

considered two different possible situations – strong interaction between

nucleons (or between other hadrons), and strong interaction in the matter of

hadrons. In the first case the pion-nucleon Yukawa interaction is often used,

according to which the role of carriers of strong interaction between nucleons

is played by virtual pions and other mesons. In the second case quantum

chromodynamics (QCD) is involved, in which hadrons are composed of quarks,

there are two quarks in each meson, and three quarks in baryons. Quarks

interact by gluons and can not exist outside hadrons

in the free form. Except two or three valence quarks, a hadron must contain

gluon clouds surrounding quarks and seas of virtual particles such as

quark-antiquark and electron-positron pairs, W and Z bosons. In QCD gluons are

considered the carriers of strong interaction, and the interaction between

nucleons is treated as a residual effect of the quark gluon fields that goes

beyond hadrons. As a result, the forces between two nucleons must be much less

than the forces between the quarks inside these nucleons.

At present the description of strong interaction between

nucleons through virtual pions to some extent looks archaic and does not seem

satisfactory. For example, it is unclear at what point between nucleons these

virtual pions should appear, what is the mechanism of their origin and

subsequent action. How can the momentum transfer from virtual pions either

attract nucleons, or repel them depending on the distance between the nucleons?

Due to what does the tensor component of nuclear forces, which is not purely

radial, arise? From a philosophical point of view, reduction of the interaction

between elementary particles to other elementary particles seems rather an

artificial device, than description of the essence of phenomena.

QCD also has its own problems analyzed in the model of quark quasiparticles. Among the

main problems are: introducing into the Standard theory many new unexplained

entities and adjustable parameters; considering interactions as point events

with quarks and bosons of point sizes and subsequent discrepancy in solutions;

unobservability of free quarks and gluons, indicating that they are

quasiparticles; color confinement as retention of color charge in hadrons, and

asymptotic freedom of quarks at short distances between them; different masses

of quarks with equal spins and two fixed values of the fractional elementary

charge; the reason for collapse of massive quarks; specification of

defragmentation method and hadronization of jets with obligatory conversion of

various color quarks into colorless hadrons; the origin of quantum numbers of

quarks, etc.

Gravitational model

Origin of mass

In the Standard model it is assumed that quarks, leptons,

W and Z bosons acquire mass through the

mechanism of spontaneous symmetry breaking and Higgs bosons. After that hadrons

consisting of quarks also become massive. If we proceed from the theory of Infinite Hierarchical Nesting of Matter,

the mass appears as an intrinsic property of material particles that occurs as

a result of Le Sage's theory of gravitation. [1] [2]

At the level of elementary particles strong gravitation influences the

scattered matter, forming objects, containing different amounts of substance.

Further, these objects evolve similarly to the main sequence stars, turning into low-mass particles like

nuons and in nucleons. According to the substantial neutron model, neutrons appear

first, and then protons and electrons emerge as a result of beta decay.

At

the level of stars neutron corresponds to a neutron star, proton corresponds to a magnetar, pions correspond to neutron stars with minimum mass

decaying in time, [3] and nuons correspond to white dwarfs. [4] Discreteness of masses of these objects

is defined by a narrow range of masses, in which formation of these objects is

possible in the field of strong (or, respectively, ordinary) gravitation

according to the equation of their matter state.

The reason of mass and its inertia in the general case is

interaction of gravitons with matter. This interaction leads to attraction of

bodies and to the concept of gravitational mass. At the same time, in case of

acceleration of bodies relative to the fluxes of gravitons inertial mass and

the corresponding inertial force appear. Taking into account the similarity of matter levels and SPФ symmetry, such description of

gravitation is universal for all levels of matter. Meanwhile, in general

relativity, mass is considered as the consequence of curvature of spacetime

around the matter and in elementary particle physics the Higgs mechanism is

introduced to describe the mass. As we can see, in the latter case,

representation of mass is ambiguous and depends strongly on the size and mass

of the objects.

The estimate of the mass and sizes of nucleons can be

obtained in the same way which was used in the study of properties of neutron

stars based on the principles of quantum mechanics. [5]

From comparison of the gravitational binding energy of the star and the quantum

mechanical energy of matter (expressed by Planck constant) we obtain formulas

for the mass and radius of the star. Similar formulas are used for nucleons as

the analogues of neutron stars. It turns out that the mass and radius of

nucleons are determined by quantum properties of their matter and depend on the

value of strong gravitational constant.

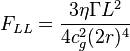

For connection of the radius and mass of the proton the following formula is

obtained: [6]

![]()

where ![]() is

a constant depending on the properties of the proton matter.

is

a constant depending on the properties of the proton matter.

Charge

The electromagnetic field, along with gravitational, is

the fundamental force field. Natural objects, containing matter at low density

and low energy of interaction, are generally neutral due to the compensation of

positive and negative charges of the matter. Charged objects occur when the

carriers of charge of a single sign are removed from (or added to) them.

Characteristic and widespread process is acquisition of a positive charge by

the proton and formation of a negatively charged electron in beta decay due to

reactions of weak interaction occurring in the neutron matter. The analysis of

energies in the proton shows that the proton charge has the maximum possible

value when the density of zero electromagnetic energy is comparable to the

energy density of strong gravitation. [6]

Equality of the charge of proton and electron follows from the nature of

neutron beta decay and takes place in every point of the Universe.

Secondary character of mass and charge of the electron in

the hydrogen atom with respect to the proton follows from substantial electron model. In particular,

the electron matter must have the charge equal to the charge of the proton, to

ensure electrical neutrality of the atom. At the same time the mass of the

electron must be of such value that its attraction to the nucleus in the strong

gravitational field must be equal to the electric force between the charges of

the nucleus and the electron. In addition, there are two almost identical

forces: repulsion of the charged matter of the electron cloud from itself, and

the centrifugal force of rotation. The sum of these four forces is zero in

stationary rotation of the electron cloud, which allows determining the strong

gravitational constant. In the process of nucleosynthesis of more massive atoms

from hydrogen atom each time interaction of neutrons, protons and electrons

takes place. It helps to understand the origin of the elementary charge and the

necessity to use it in elementary particle physics and in atomic physics as the

standard unit of charge. Thus, the origin of mass and charges of elementary

particles does not require introduction of hypothetical fields like the Higgs

field.

Energy

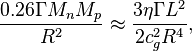

Since at the level of elementary particles the main force

is assumed strong gravitation, it

allows us to calculate total energy of hadron of nucleon type, which is up to

sign equal to the binding energy of the hadron matter: [3] [6]

![]()

Here ![]() for

objects like nucleons and neutron stars,

for

objects like nucleons and neutron stars, ![]() is the strong gravitational constant,

is the strong gravitational constant,

![]() and

and ![]() are the mass and radius of the hadron.

are the mass and radius of the hadron.

Relation (1) can be used to estimate approximately the

particle radius by its known mass, rewriting (1) in the form ![]() where

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the mass and radius of the proton. If we substitute the obtained radii

of the particles into (2), we obtain the gravitational binding energies of the

particles shown in the Table. [6]

are the mass and radius of the proton. If we substitute the obtained radii

of the particles into (2), we obtain the gravitational binding energies of the

particles shown in the Table. [6]

|

Characteristics

of proton, pion and muon |

||||

|

Particle |

Mass-energy, MeV |

Mass, 10–27 kg |

Radius, 10–16

m |

Binding energy |

|

Proton p+ |

938.272029 |

1.6726 |

8.7 |

938.272 |

|

Meson |

600 |

1.1 |

10 |

354 |

|

Pion π+ |

139.567 |

0.249 |

16.4 |

11 |

|

Muon μ+ |

105.658 |

0.188 |

10900 |

0.095 |

The particle masses in Table are obtained by dividing the

mass-energy converted from MeV to J, by the squared speed of light. The

mass-energy corresponds to the rest energy in the special relativity, and is

directly proportional to the mass (see the mass–energy equivalence). In

contrast to this, the total energy of the particle is calculated by summing the

potential energy of strong gravitation and the internal kinetic energy of

particle matter, the absolute value of the total energy is equal to the binding

energy or the energy required to scatter the particle matter to infinity with

zero velocity. According to the Table the binding energy of pion matter in the

strong gravitational field is one order of magnitude less than the rest energy,

which is the consequence of low density of the pion matter.

The laws of conservation of energy and momentum in

reactions with elementary particles in the special theory of relativity are as

follows:

![]()

![]()

where before the interaction there are n particles, and

after the interaction the number of particles is m, and there is a possibility

that ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are corresponding mass and momentum of particles,

are corresponding mass and momentum of particles, ![]() is

the speed of light.

is

the speed of light.

On the other hand, the energy balance can be written in

such a way as to explicitly include the change in the total energy of

particles: [6]

![]()

where ![]() is the

total energy of the k-th particle in the field of

strong gravitation,

is the

total energy of the k-th particle in the field of

strong gravitation, ![]() is

the radius of the k-th particle,

is

the radius of the k-th particle, ![]() is the kinetic energy of the k-th particle in the special theory of relativity, and during

interaction the energy of strong gravitation

is the kinetic energy of the k-th particle in the special theory of relativity, and during

interaction the energy of strong gravitation ![]() can be released (or, conversely, be added) which is associated with change

in the radii and masses of particles, as well as the energy of the emerging

electromagnetic and neutrino emission

can be released (or, conversely, be added) which is associated with change

in the radii and masses of particles, as well as the energy of the emerging

electromagnetic and neutrino emission ![]() .

.

Structure of nucleons

According to the substantial

neutron model and the substantial

proton model, the difference between neutron and proton besides mass and

charge is mainly in the difference in their internal electromagnetic structure.

Thus, in neutron the space charge separation is assumed, the center of the

neutron is positively charged, and the shell is negative. The rotation of the

space charge creates a negative magnetic moment of neutron, directed opposite

to the spin.

To connect the medium pressure ![]() and the mass density

and the mass density ![]() of

nucleon in the first approximation, we can write down:

of

nucleon in the first approximation, we can write down:

![]()

where ![]() in SI units is the coefficient,

found by the radius of nucleon, its mass and strong gravitational constant. [6] In the self-consistent model that takes into

account the density distribution, the rest energy, magnetic moment and the

conditions of limiting rotation, the ratio of the central proton mass density

to its average density is 1.57. [7]

in SI units is the coefficient,

found by the radius of nucleon, its mass and strong gravitational constant. [6] In the self-consistent model that takes into

account the density distribution, the rest energy, magnetic moment and the

conditions of limiting rotation, the ratio of the central proton mass density

to its average density is 1.57. [7]

From the point of view of the matter state, instead of

three quarks and indefinite number of gluons inside nucleons we expect up to ![]() of

smallest particles called praons.

According to the theory of Infinite Hierarchical Nesting of Matter, praons have the same status in nucleons as

nucleons themselves in neutron stars. This explains why in collisions even with

highest energies we observe not gas of quarks and gluons, but jets of almost

perfect liquid hadronic matter. [8] [9]

of

smallest particles called praons.

According to the theory of Infinite Hierarchical Nesting of Matter, praons have the same status in nucleons as

nucleons themselves in neutron stars. This explains why in collisions even with

highest energies we observe not gas of quarks and gluons, but jets of almost

perfect liquid hadronic matter. [8] [9]

In the above picture de

Broglie wavelength of moving nucleons and other elementary particles can be

explained as a consequence of the relativistic transformation of wavelength of

the internal oscillations of the fundamental fields potentials of the particles

in the laboratory frame of reference.

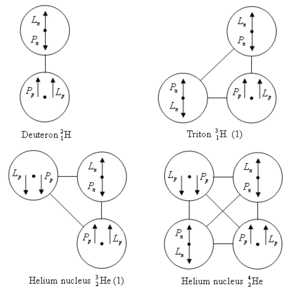

Deuteron

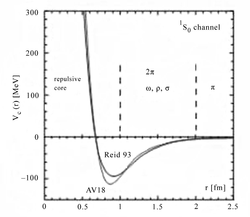

Deuteron is the simplest nucleus consisting of two

nucleons – proton and neutron. In Figure P2 there are two examples of modern

potential of nuclear force depending on distance ![]() , which can be considered equal to the

distance from the center of mass of the system of two nucleons to the center of

one of the nucleons. From internucleon potential, understood as interaction

energy of two nucleons, we can proceed to the force acting on the nucleon,

according to the formula:

, which can be considered equal to the

distance from the center of mass of the system of two nucleons to the center of

one of the nucleons. From internucleon potential, understood as interaction

energy of two nucleons, we can proceed to the force acting on the nucleon,

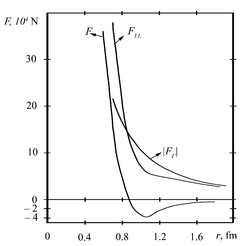

according to the formula: ![]() The graph of this force is shown in

Figure P3 for the potential AV18.

The graph of this force is shown in

Figure P3 for the potential AV18.

In the gravitational model of strong interaction the

force ![]() between nucleons in the first approximation

is presented as the difference between the force of spin repulsion

between nucleons in the first approximation

is presented as the difference between the force of spin repulsion ![]() and the magnitude of gravitational force of attraction

and the magnitude of gravitational force of attraction ![]() : [4]

: [4]

![]()

where ![]() is

the gravitational torsion field from one

nucleon, which acts on the effective spin

is

the gravitational torsion field from one

nucleon, which acts on the effective spin ![]() of

the other nucleon,

of

the other nucleon, ![]() and

and ![]() are the masses of neutron and proton, respectively,

are the masses of neutron and proton, respectively, ![]() is the distance between the centers of

nucleons,

is the distance between the centers of

nucleons, ![]() is

the coefficient, the estimate of which for the case of two nucleons is

is

the coefficient, the estimate of which for the case of two nucleons is ![]() as a result of exponential absorption of

gravitons in the matter of nucleons, and for particles of lower density it is

as a result of exponential absorption of

gravitons in the matter of nucleons, and for particles of lower density it is ![]() .

.

Spin ![]() includes the initial nucleon spin, and the

spin induced by another nucleon by means of gravitational

induction. The formula for the repulsive force of nucleon spins is: [4]

includes the initial nucleon spin, and the

spin induced by another nucleon by means of gravitational

induction. The formula for the repulsive force of nucleon spins is: [4]

,

,

where ![]() is

the speed of propagation of gravitational effect (the speed of gravity), which

is close to the speed of light,

is

the speed of propagation of gravitational effect (the speed of gravity), which

is close to the speed of light, ![]() is

the coefficient depending on the distance of nucleons interaction in the

deuteron.

is

the coefficient depending on the distance of nucleons interaction in the

deuteron.

Since in Figure P3 at ![]() fm the force

fm the force ![]() vanishes, we can estimate the distance

between the surfaces of nucleons:

vanishes, we can estimate the distance

between the surfaces of nucleons: ![]() fm. The described state with opposite

nucleon spins has small binding energy of about 69 keV and therefore is

unstable. If we locate nucleons in this state on the plane, the spins of

nucleons will be perpendicular to the plane and opposite to each other.

fm. The described state with opposite

nucleon spins has small binding energy of about 69 keV and therefore is

unstable. If we locate nucleons in this state on the plane, the spins of

nucleons will be perpendicular to the plane and opposite to each other.

From Figure P3 we see that when ![]() , that is in nucleons’ contact, the spin

repulsive force from the torsion field is equal to the gravitational force of

attraction. At smaller distances a rapidly growing force of repulsion emerges.

We can assume that the main contribution is made by the magnetic force of

repulsion and the force of internal pressure in the matter of nucleons.

, that is in nucleons’ contact, the spin

repulsive force from the torsion field is equal to the gravitational force of

attraction. At smaller distances a rapidly growing force of repulsion emerges.

We can assume that the main contribution is made by the magnetic force of

repulsion and the force of internal pressure in the matter of nucleons.

At distances from ![]() m to

m to ![]() m the force from the torsion field decreases according to the

dependence

m the force from the torsion field decreases according to the

dependence ![]() , where

, where ![]() .

If the nucleons (neutron and proton), considered as points were

interacting only by torsion fields from their constant spins, the dependence on

the distance in the formula for the force of spin interaction would have the

form

.

If the nucleons (neutron and proton), considered as points were

interacting only by torsion fields from their constant spins, the dependence on

the distance in the formula for the force of spin interaction would have the

form ![]() .

However, when two nucleons approach each other in deuteron formation,

additional effects can occur. Firstly, in case of the same direction of spins,

due to the effect of gravitational induction both nucleons will rotate each

other as they approach, with increasing of their spins. Secondly, besides

gravitational forces there are also electromagnetic ones, which are the forces

of repulsion of magnetic moments in deuteron (and the magnitude of magnetic

moments due to various effects can also change as the nucleons approach each

other). All this leads to the fact that in the effective force

.

However, when two nucleons approach each other in deuteron formation,

additional effects can occur. Firstly, in case of the same direction of spins,

due to the effect of gravitational induction both nucleons will rotate each

other as they approach, with increasing of their spins. Secondly, besides

gravitational forces there are also electromagnetic ones, which are the forces

of repulsion of magnetic moments in deuteron (and the magnitude of magnetic

moments due to various effects can also change as the nucleons approach each

other). All this leads to the fact that in the effective force ![]() of

nucleons repulsion the exponent increases up to the values greater than

of

nucleons repulsion the exponent increases up to the values greater than ![]() . Thus, from a qualitative point of view,

the gravitational forces of attraction and the forces of spins interaction and

the electromagnetic forces can explain the nuclear forces at short distances.

. Thus, from a qualitative point of view,

the gravitational forces of attraction and the forces of spins interaction and

the electromagnetic forces can explain the nuclear forces at short distances.

At distances greater than ![]() m the force

m the force ![]() in Figure P3, built as the sum of the force

in Figure P3, built as the sum of the force ![]() from internucleon potential and the magnitude of the gravitational force

from internucleon potential and the magnitude of the gravitational force ![]() , undergoes a strange kink, with a

significant change in the speed of its decrease with distance. This is due to

the inaccuracy of internucleon potential of the Standard model, according to

which the interaction between nucleons occurs by means of special carriers –

virtual mesons (in Figure P2 the areas are indicated where interactions with

two pions 2π, with mesons ρ, ω, σ, and one meson π are taken into account) .

Until now, the basis for calculation of the potential at these distances is the

Yukawa potential of the following form:

, undergoes a strange kink, with a

significant change in the speed of its decrease with distance. This is due to

the inaccuracy of internucleon potential of the Standard model, according to

which the interaction between nucleons occurs by means of special carriers –

virtual mesons (in Figure P2 the areas are indicated where interactions with

two pions 2π, with mesons ρ, ω, σ, and one meson π are taken into account) .

Until now, the basis for calculation of the potential at these distances is the

Yukawa potential of the following form:

![]()

where ![]() is

some effective charge of strong interaction,

is

some effective charge of strong interaction, ![]() is the mass of the particle – the carrier of interaction,

is the mass of the particle – the carrier of interaction, ![]() is the Dirac constant.

is the Dirac constant.

For the pion the quantity ![]() in the exponent is equal to one

with

in the exponent is equal to one

with ![]() m, with masses of heavier mesons the distance decreases. The force from the

Yukawa potential, which has the character of attraction, equals:

m, with masses of heavier mesons the distance decreases. The force from the

Yukawa potential, which has the character of attraction, equals:

![]()

At such distances ![]() , where

, where ![]() , the force

, the force ![]() decreases slowly enough, in proportion

decreases slowly enough, in proportion ![]() .

This creates a kink in Figure P3 for the force of spins interaction

.

This creates a kink in Figure P3 for the force of spins interaction ![]() . At the same time, the gravitational

force

. At the same time, the gravitational

force ![]() changes in proportion

changes in proportion ![]() , that is, faster than the force

, that is, faster than the force ![]() from the Yukawa potential at the segment

from the Yukawa potential at the segment ![]() m.

m.

If we proceed from the gravitational and electromagnetic

interactions, the formula for the total energy of interaction between nucleons

in the deuteron must include gravitational energy, the energy of spins and

spin-orbital gravitational interactions, the energy of spin-spin and

spin-orbital interaction of the magnetic moments taking into account the

possible effect of electromagnetic induction, increment of kinetic and

rotational energy of nucleons, which may depend on the distance between the

nucleons, due to the interaction of the gravitational and electromagnetic

forces. Almost all of these energies can contribute to the creation of the

effective force between nucleons.

In the deuteron we can assume that the nucleons are on

the common axis of rotation, and the nucleon spins are directed in one side of

the axis. Then, the magnetic moments of the proton and neutron are opposite,

corresponding to the magnetic moment of the deuteron. In the absence of orbital

rotation, the entire spin of the deuteron will consist of the nucleons spin.

Considering only the main components of energies and forces, in equilibrium, at

a small distance ![]() between the centers of the nucleons, the

following relations hold:

between the centers of the nucleons, the

following relations hold:

![]()

where ![]() is

the proton radius as the measure of the nucleon radius,

is

the proton radius as the measure of the nucleon radius,  is the internal energy of the torsion

field in the deuteron per one nucleon,

is the internal energy of the torsion

field in the deuteron per one nucleon,  is the internal energy of the torsion field of free nucleon,

is the internal energy of the torsion field of free nucleon,  is the

energy of two spins in the field of each other, or doubled energy of one spin

in the external torsion field from the second spin,

is the

energy of two spins in the field of each other, or doubled energy of one spin

in the external torsion field from the second spin, ![]() is the change in rotational kinetic

energy of nucleons,

is the change in rotational kinetic

energy of nucleons, ![]() is the moment of inertia of the nucleon,

is the moment of inertia of the nucleon, ![]() MeV is the binding energy of the deuteron.

MeV is the binding energy of the deuteron.

In the presented balance of forces in the first

approximation only the force of gravitational attraction of nucleons and the

force of spins repulsion ![]() are taken into account. The solution for the

balance of forces and energies is the value

are taken into account. The solution for the

balance of forces and energies is the value ![]() m between the adjacent surfaces of

nucleons. [4] In this case, the particles

of hadron matter inside nucleons on the average have the speed almost equal to

the speed of light.

m between the adjacent surfaces of

nucleons. [4] In this case, the particles

of hadron matter inside nucleons on the average have the speed almost equal to

the speed of light.

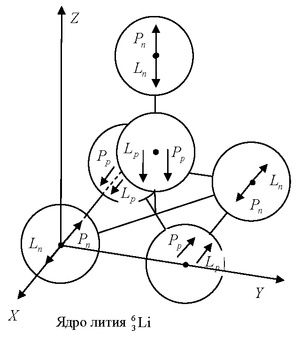

Atomic nuclei

The analysis of the equilibrium state of nucleons in the

deuteron allows us to formulate the following conditions for stability of

atomic nuclei:

- Adjacent nucleons must have zero

relative rotation of the surfaces closest to each other. For example, if

nucleons rotate as though located on the same axis, they must rotate

synchronously. Otherwise, magnetic forces and torsion forces appear

leveling the angular rotational velocity.

- Another necessary condition is

that the adjacent nucleons must have such direction of spins that there

was a repulsive force between them.

- The absence of diproton and

dineutron shows that the combination with two adjacent protons or two

neutrons on a common axis of rotation in the nucleus is hardly probable,

at least for small nuclei.

Based on this, the models of triton (tritium nuclei, a

heavy isotope of hydrogen) and of other basic nuclei – helium and lithium are

built. Spin-spin forces between nucleons in atomic nuclei explain the Pauli

exclusion principle, according to which identical fermions that are close,

cannot have the same quantum numbers. In particular, spins of identical

nucleons in the presented models of atomic nuclei are in opposite directions.

It is known that triton turns into the light helium

nucleus with half-decay period 12.32 years due to beta decay. This can be

presented in the way that the left neutron of the triton in Figure P4,

undergoing beta decay, turns into a proton and moves to the position taken by

the left proton in the nucleus of the light helium in Figure P4. In this case, direction of the

nucleon spin does not change, ![]() , but magnetic moment of the

neutron

, but magnetic moment of the

neutron ![]() is transformed into oppositely

directed magnetic moment of the proton

is transformed into oppositely

directed magnetic moment of the proton ![]() .

.

For the motion of the nucleon it needs momentum which

arises from the emission of electron antineutrino in beta decay of the neutron.

As it is shown in the substantial neutron

model, antineutrino flies toward the spin of the decaying neutron and

pushes the neutron in the opposite direction. After this, the triton turns into a nucleus of light helium

Nuclear binding energy

With the help of expression for gravitational energy we

can qualitatively show the need for the growth of specific nuclear binding

energy (binding energy per nucleon) with growth of mass of the nucleus.

Since in atomic nucleus the nucleon density only slightly

depends on the number of nucleons, it means the approximate equality of volumes

per one nucleon in different nuclei. It is usually assumed that the average

distance between nucleons in nuclei is of the order of ![]() m. If we denote the total binding

energy of nucleus by

m. If we denote the total binding

energy of nucleus by ![]() , with a small number of nucleons this

energy must be proportional to gravitational energy

, with a small number of nucleons this

energy must be proportional to gravitational energy ![]() of all the nucleons of the nucleus in the field of strong gravitation.

of all the nucleons of the nucleus in the field of strong gravitation.

If the nucleus consists of ![]() nucleons, the nuclear mass is

nucleons, the nuclear mass is ![]() ,

the volume per one nucleon is equal to

,

the volume per one nucleon is equal to ![]() ,

the volume of the nucleus is

,

the volume of the nucleus is ![]() , then the nucleus radius

, then the nucleus radius ![]() will be proportional to

will be proportional to ![]() . Hence the specific binding energy and

the specific gravitational energy will be proportional to the quantity:

. Hence the specific binding energy and

the specific gravitational energy will be proportional to the quantity: ![]()

The dependence of the specific binding energy on the

number of nucleons in the nucleus as ![]() in

general is confirmed: if for the deuteron it is equal to 1.1 MeV/nucleon, then

for the nuclei with

in

general is confirmed: if for the deuteron it is equal to 1.1 MeV/nucleon, then

for the nuclei with ![]() the specific binding energy is equal to 8

MeV/nucleon. With further increase of

the specific binding energy is equal to 8

MeV/nucleon. With further increase of ![]() the

specific binding energy reaches the value of 8.7 MeV/nucleon, and then slowly

decreases (approximately up to about 7.6 MeV/nucleon for the nucleus of

uranium). Such a dependence is explained by the growing influence of electrical

energy of protons repulsion with the growth of

the

specific binding energy reaches the value of 8.7 MeV/nucleon, and then slowly

decreases (approximately up to about 7.6 MeV/nucleon for the nucleus of

uranium). Such a dependence is explained by the growing influence of electrical

energy of protons repulsion with the growth of ![]() , which reduces the binding energy. In

addition, from the Le Sage’s theory of gravitation the saturation effect of

strong gravitational energy follows with

, which reduces the binding energy. In

addition, from the Le Sage’s theory of gravitation the saturation effect of

strong gravitational energy follows with ![]() .[4] As a consequence of this effect in case of further increase in the mass of

the nucleus the nucleons added to the nucleus will have the same energy, and

the potential of gravitational field remains almost unchanged. The

gravitational pressure in the nucleus is fixed and stops growing,

correspondingly, the average distances between the nucleons stop changing too.

This result is consistent with the fact that with

.[4] As a consequence of this effect in case of further increase in the mass of

the nucleus the nucleons added to the nucleus will have the same energy, and

the potential of gravitational field remains almost unchanged. The

gravitational pressure in the nucleus is fixed and stops growing,

correspondingly, the average distances between the nucleons stop changing too.

This result is consistent with the fact that with ![]() the maximum of the specific binding energy of

atomic nuclei is reached.

the maximum of the specific binding energy of

atomic nuclei is reached.

Composite hadrons

All hadrons, including mesons and baryons, can be divided

into three groups. The first group includes the simplest quasi-stable hadrons

like pions and nucleons, having long lifetime. These hadrons can be considered

as independent particles experiencing decay due to weak interaction (except for

stable proton). The second group consists of long-lived strange, charmed and

beautiful particles, and the third group includes resonances, whose lifetime is

almost equal to the time of particles’ transit near each other at their close

interaction. As shown in the model of quark

quasiparticles, strange particles can be represented as composite hadrons

of simple hadrons of the first group. [6] For

example, hyperon Λ is assumed to consist of proton and pion rapidly rotating

next to each other along one axis, held by strong gravitation and spin torsion

fields. In calculating the equilibrium conditions, the equations for the forces

and energies are used, similar to those presented above for the deuteron.

Hypothetical composition of other strange hadrons is as

follows: hyperon Σ is a compound of

neutron with pion; Ξ includes proton and two pions; three or four pions with

proton make up Ω-baryon. K-mesons are compounds of three pions and have the

following compositions:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Different combinations of pions in neutral kaon can

explain different lifetimes of ![]() and

and ![]() states. In contrast to atomic nuclei, compounds of nucleons and pions (or

pions with each other) can not be stable, and over

time they disintegrate. The same applies to charmed and beautiful hadrons.

states. In contrast to atomic nuclei, compounds of nucleons and pions (or

pions with each other) can not be stable, and over

time they disintegrate. The same applies to charmed and beautiful hadrons.

There are many works in which resonances are presented

not as interactions of quarks but as dynamically bound short-lived states of

simpler hadrons. For example, hyperon Λ(1405) is considered as dynamic bound

state of nucleon and kaon, [12] and scalar mesons f(980) and a(980) are considered as a molecule of kaon

and antikaon. [13] Hadronic molecules of kaon, antikaon and nucleon are discussed in [14] by solving the Schrödinger equation for

the wave function of three particles and using two interaction potentials

assumed in the model. There are strong proofs that many resonant states N, Δ,

Λ, Σ, Ξ, Ω are dynamically bound states

of vector mesons (of ρ and ω type) with baryons belonging to baryon octet with

nucleons and to decuplet with Δ. [15]

Weak interaction

In gravitational

model of strong interaction masses as well as charges of elementary particles

are explained by the properties and the structure of particles’ matter, and by

the action of strong gravitation and electromagnetic forces in this matter.

Under the action of these forces ordering of matter particle takes place, and this

matter has the ability to transform slowly in reactions of weak interaction.

Thus weak interaction at the level of elementary particles is reduced again to

weak interaction, but at the level of minute particles that make up the matter

of elementary particles.

The examples of description of reactions of weak

interaction in the matter of elementary

particles are shown in the model of quark

quasiparticles, in the substantial

neutron model and in the substantial

proton model. In particular it is shown that neutrinos of one basic level

of matter are two-component and consist of fluxes of electron neutrinos and

antineutrinos of the lower basic level of matter.

This means that weak interaction can be explained not

with the help of special field quanta of the type of W and Z bosons, but

represent as the property of matter to change naturally in conditions of

maximum possible density of matter and energy.

Thus, it is expected that during the time of the order of 2•1015

years neutron stars must undergo ![]() -decay, with formation of magnetars and

ejection of negatively charged shells (similarly to neutrons decomposing with

formation of protons, electrons and electron antineutrinos).

-decay, with formation of magnetars and

ejection of negatively charged shells (similarly to neutrons decomposing with

formation of protons, electrons and electron antineutrinos).

Coupling constants

Main source: Coupling

constant

To compare gravitational, weak, electromagnetic and

strong interactions the energies of corresponding forces are usually

considered, acting on proton matter taking into account

its mass and charge, in the field of other proton. For energies we can write

down:

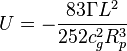

![]()

![]()

where ![]() is

gravitational constant,

is

gravitational constant, ![]() is

the proton mass,

is

the proton mass, ![]() is

distance between the centers of protons,

is

distance between the centers of protons, ![]() is

Fermi constant of weak interaction,

is

Fermi constant of weak interaction, ![]() is the speed of light,

is the speed of light, ![]() is

mass of virtual W or Z boson, which is considered the carrier of weak interaction,

is

mass of virtual W or Z boson, which is considered the carrier of weak interaction, ![]() is

the proton charge, equal to elementary charge,

is

the proton charge, equal to elementary charge, ![]() is

electric constant,

is

electric constant, ![]() is

the charge of strong interaction,

is

the charge of strong interaction, ![]() is

the mass of virtual particle (mostly pion), which is supposed carrier of strong

interaction.

is

the mass of virtual particle (mostly pion), which is supposed carrier of strong

interaction.

The expressions for corresponding coupling constants

follow from the relations for energy:

![]()

![]()

The coupling constant of electromagnetic interaction ![]() is

called fine structure constant. The

charge of strong interaction

is

called fine structure constant. The

charge of strong interaction ![]() and the Fermi constant

and the Fermi constant ![]() are axiomatically introduced into Standard theory to describe experimental

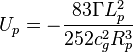

results. If we proceed from the notion of strong gravitation, the interaction

energy of two nucleons and the coupling constant will equal: [6]

are axiomatically introduced into Standard theory to describe experimental

results. If we proceed from the notion of strong gravitation, the interaction

energy of two nucleons and the coupling constant will equal: [6]

![]()

where ![]() is

strong gravitational constant,

is

strong gravitational constant, ![]() for the case of two nucleons.

for the case of two nucleons.

This shows that the coupling constant ![]() of

strong gravitation is of the same order of magnitude as the coupling constant

of

strong gravitation is of the same order of magnitude as the coupling constant ![]() of strong interaction. In atomic nuclei the equilibrium of nucleons is

achieved due to attraction from the strong gravitational field and repulsion

from gravitational torsion fields, and the coupling constants of both

components of gravitational field (gravitational field strength of strong gravitation and gravitational torsion field ) are leveled

in magnitude.

of strong interaction. In atomic nuclei the equilibrium of nucleons is

achieved due to attraction from the strong gravitational field and repulsion

from gravitational torsion fields, and the coupling constants of both

components of gravitational field (gravitational field strength of strong gravitation and gravitational torsion field ) are leveled

in magnitude.

Unification of interactions

In Standard model the gauge approach of quantum field

theory is used, when for each type of interaction (gravitational, electromagnetic,

weak and strong) their own fields and gauge bosons-quanta, that carry the

interaction, are introduced. Gravitons, photons, W and Z bosons, gluons, and

particles such as Higgs boson appear this way. At present, weak and

electromagnetic interactions of elementary particles, despite their significant

differences, are discussed by electroweak theory based on the unified

mathematical formalism. In future it is planned to add in the common scheme

strong (Grand Unified Theory) and gravitational interaction (theory of

everything).

Disadvantage of this approach is its focus only on

description of the observed processes, without penetration into the essence of

phenomena. So far, there are no specific mechanisms that explain how the forces

of attraction or repulsion between particles emerge due to the action of any

gauge bosons, such as photons. There is a gap between the facts that single

accelerated charges generate real electromagnetic emission that transfers

energy and theoretically is considered as a set of photons or partial waves,

and there is no such emission near fixed charges although the adjacent charges

somehow interact with each other. To create a unified picture it is necessary

that photons could explain not only free electromagnetic emission but also the

static electromagnetic field. However, in case of purely electrostatic and

magnetostatic fields there are no electromagnetic energy fluxes, the Poynting

vector at each point is zero, and thus the possible direction of the motion of

photons can not be determined. Introducing into the

theory the idea of virtual particles does not help, because interactions with

virtual photons, gluons, W and Z bosons, quark-antiquark pairs,

electron-positron fields, etc. can not be considered

as the ultimate solution.

As shown above, strong interaction at the level of

elementary particles can be reduced to the action of strong gravitation and

spin gravitational forces from torsion fields, with addition from

electromagnetic forces. The same forces and the corresponding interaction will

be at the level of the stars, with substitution of strong gravitation by

ordinary gravitation. It is considered that gravitation at the macro level in

general must be described by relativistic theories such as general theory of

relativity (GTR) or covariant theory of

gravitation (CTG). But in GTR gravitation is reduced to curvature of

spacetime and is not a physical force, whereas in CTG the cause of

gravitational force is assumed the action of gravitons, considered in Le Sage’s

theory of gravitation. Gravitons act on matter regardless of the number and density of this matter and the effects emerging in strong fields near massive bodies, such as the

effect of time dilation, are reduced to influence of gravitons on the

properties of electromagnetic waves (photons) used for measurements. The latter

means dependence of results of measurements of length and time on the

measurement procedure by means of light signals, with the constant picture of

interaction of gravitons with matter. In this case,

the effects of GTR, including the hypothetical black holes, are external, and

do not reflect real essence of gravitational interaction.

In the weak fields, where dependence on the measurement

procedure can be neglected, GTR turns to gravitoelectromagnetism

and CTG – to Lorentz-invariant theory of

gravitation (LITG). It turns out that in LITG and in

gravitoelectromagnetism the equations of gravitational field are almost exactly the same and are similar in form to the equations

of the electromagnetic field in electrodynamics, which is emphasized in Maxwell-like gravitational equations.

Apparently, the similarity of equations for both fields is not accidental.

Relationship between electromagnetism and gravitation may be that part of gravitons are photons

emitted by charged praons – the carriers of matter, from which the matter can be formed, which is part of the matter of elementary particles. [6]

Representation of gravitons in the form of photons was

used to represent the formula of gravitational force, as a result of Compton

scattering of photons in matter. [16] On the other hand, emission of energy of

supernovae in formation of neutron stars is almost entirely realized through

neutrino emission, and not in the form of expected gravitational waves. That,

and the similar penetrating ability of particles give the reason to assume that

neutrinos of one level of matter are gravitational quanta or gravitons of

higher levels of matter. Comparison of the energy density of neutrino emission

in supernova and the similar neutrino emission from matter of neutron which is formed, taking into account the coefficients of

similarity in the theory of similarity of

matter levels, shows that the gravitons of ordinary gravitation can be

neutrinos generated by matter, the carriers of which correspond to

elementary particles in the same way as elementary particles correspond to

stars, or can be smaller by one basic level of matter. [6] If gravitons are both photons and neutrinos, then there is may be the

case when the neutrino is a type of electromagnetic radiation. The difference between photon and

neutrino is that neutrino is two-component emission with opposite polarization

of the components. In this case, photon and neutrino are composed of the

corresponding fluxes of tiny quanta of emission.

In the above picture

electromagnetic and gravitational fields are fundamental and similar to each

other both in the form of equations for the field and the acting forces, and in

their origin associated with the dynamic action of particles of electrogravitational vacuum. For example, gravitational quanta of one

level of matter are able to compress the matter into massive objects of higher level of matter up to such density that as

a result emission of new, more powerful gravitational and electromagnetic

quanta is possible, as well as emission of charged particles such as cosmic

rays. After that, the emerged relativistic particles, neutrinos and photons

interact in a similar way with the matter of higher

levels of matter, and so the process goes on. At the same time, there is a

reverse process of energy dissipation and splitting of quanta.

Adding to the fluxes of gravitons

by Le Sage’s model the fluxes of charged particles of different signs allows us

not only to derive the Newton’s formula of gravitation and to explain the

origin of gravitational force, but also to understand the origin of electrostatic

force between two charges. [17] [2] [18] [19]

Strong and weak interactions by

their nature are not fundamental field interactions, characteristic of each

object separately. This is due to the fact that the first of them depends on combination

of fundamental fields in the interaction of objects with each other, and the

second – on the interaction of internal fields in the matter of objects with the total gravitational and

electromagnetic fields of these objects, or with external emission, leading to matter transformation.

It was shown that the electromagnetic and gravitational fields, acceleration

field, pressure field, dissipation

field, strong interaction field, weak

interaction field, and other vector fields acting on matter and its particles,

are components of general field and can be described by the same equations. [20] [21] Thus, the general field becomes a

good candidate for a unified field theory suitable for describing any

phenomena.

References

- Fedosin S.G. Model

of Gravitational Interaction in the Concept of Gravitons. Journal of

Vectorial Relativity, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 1-24

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.890886 .

- 2.0 2.1 Fedosin S.G. The

graviton field as the source of mass and gravitational force in the

modernized Le Sage’s model. Physical Science International

Journal, ISSN: 2348-0130, Vol. 8, Issue 4, pp. 1-18 (2015). http://dx.doi.org/10.9734/PSIJ/2015/22197.

- 3.0 3.1 Fedosin S.G. (1999), written at Perm, pages 544, Fizika i filosofiia podobiia ot preonov do metagalaktik,

ISBN 5-8131-0012-1.

- 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4

Sergey Fedosin, The physical theories and

infinite hierarchical nesting of matter, Volume 1,

LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, pages: 580, ISBN-13: 978-3-659-57301-9.

- Landau L.D. On the theory of stars. – Phys. Z. Sowjetunion, Vol. 1, p. 285

(1932).

- 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04

6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09

Comments

to the book: Fedosin S.G. Fizicheskie teorii i beskonechnaia

vlozhennost’ materii.

– Perm, 2009, 844 pages, Tabl. 21, Pic. 41, Ref.

289. ISBN 978-5-9901951-1-0. (in Russian).

- Fedosin S.G. The

radius of the proton in the self-consistent model. Hadronic Journal, Vol. 35, No.

4, pp. 349-363 (2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.889451.

- 'Perfect'

Liquid Hot Enough to be Quark Soup. Brookhaven National Laboratory

News (2010). Retrieved on 2010-02-26.

- LHC

Experiments Bring New Insight into Primordial Universe. Brookhaven

National Laboratory News (2010). Retrieved on 2010-12-09.

- Ishii N., Aoki S., Hatsuda

T. The Nuclear Force from

Lattice QCD. arXiv: nucl-th

/ 0611096 v1, 28 Nov 2006.

- Яворский

Б.М., Детлаф А.А., Лебедев А.К. Справочник по

физике. – М.: Оникс, Мир и образование, 2006, 1056 с.

- R. H. Dalitz and S. F. Tuan, Phys. Rev. Lett. Vol. 2, p. 425 (1959); Annals Phys. 10, 307

(1960).

- J.D. Weinstein and N. Isgur, Phys. Rev. Lett. 48,

659 (1982); Phys. Rev. D 41, 2236 (1990).

- Daisuke Jido, Yoshiko

Kanada-En'yo. A new N* resonance as a hadronic

molecular state. 25 Jun 2009.

- Oset, E. at al. Dynamically generated resonances.

20 Jun 2009.

- Michelini Maurizio. The Physical

Reality Underlying the Relativistic Mechanics and the Gravitational

Interaction. – arXiv: physics / 0607136 v1,

14 Jul 2006.

- Fedosin

S.G. Fizicheskie

teorii i beskonechnaia vlozhennost’ materii. – Perm, 2009, 844 pages, Tabl. 21, Pic. 41, Ref. 289. ISBN 978-5-9901951-1-0.

(in Russian)

- Fedosin S.G. The

charged component of the vacuum field as the source of electric force in

the modernized Le Sage’s model. Journal of Fundamental and Applied

Sciences, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 971-1020 (2016). http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jfas.v8i3.18,

https://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.845357.

- Fedosin

S.G. On the structure of the force field in electro gravitational vacuum.

Canadian Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp.

5125-5131 (2021). http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4515206.

- Fedosin S.G. The Concept of the General

Force Vector Field. OALib Journal, Vol. 3, pp. 1-15 (2016), e2459. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1102459.

- Fedosin

S.G. Two components of the macroscopic general field. Reports in Advances of Physical Sciences, Vol. 1,

No. 2, 1750002, 9 pages (2017).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S2424942417500025.

See also

- Infinite

Hierarchical Nesting of Matter

- Similarity

of matter levels

- SPФ

symmetry

- Strong

gravitation

- Gravitational

torsion field

- De Broglie

wavelength

- Model of

quark quasiparticles

- Substantial electron model

- Substantial neutron model

- Substantial

photon model

- Substantial

proton model

- Praon

External links

|

||||||